The "Can Do" UK Armed Forces Can't Deliver

Grant Shapps needs to get real - the British Armed Forces are a mess and fooling no-one but themselves. That's neither deterrence nor value for money.

The UK’s relatively new Minister of Defence, Grant Shapps, recently enthused about the “can do” attitude of the UK’s armed forces, suggesting that this would maintain capability despite reducing numbers in the Army.

Back in the real world senior NATO commander has declared that conflict with Russia is likely within 20 years. That might be optimistic, thee German Defence Minister reckons that war with Putin’s Russia is likely in five to eight years. Worse, the increasingly likely next president of the US, Donald Trump, reckoned that NATO was dead in 2020 and he’s not talking about resurrecting it.

Sweden and Finland joining NATO has significantly increased its firepower in terms of quantity and quality, albeit at the cost of massively increasing the NATO frontier with Russia. That’s mostly artic terrain that only the Norwegians, Swedes, Finns and Russians understand or are equipped for. At best that balances out.

Who has been telling Shapps that the Armed Forces can do? If it’s the service chiefs then we really have a problem. As is blindingly obvious to anyone who can read a newspaper. Current problems include:

· The Royal Navy can’t crew its ships. Those that it can crew either shoot million dollar missiles at $20,000 drones or bump into each other.

· The Royal Air Force’s new F35 fighters are behind schedule and won’t reach full operating capability until 2025. The current ones are aging and in any case it forgot to buy key AWACS equipment on time or in sufficient quantities, so can only operate with allied support.

· The Army is even worse. At best it can field one brigade (around 5,000 troops) with a hotchpotch range of vehicles in varying states of obsolescence. Other than funerals and coronations it’s capability is such that the US Army would rather we didn’t go to war alongside them as we’re not good enough.

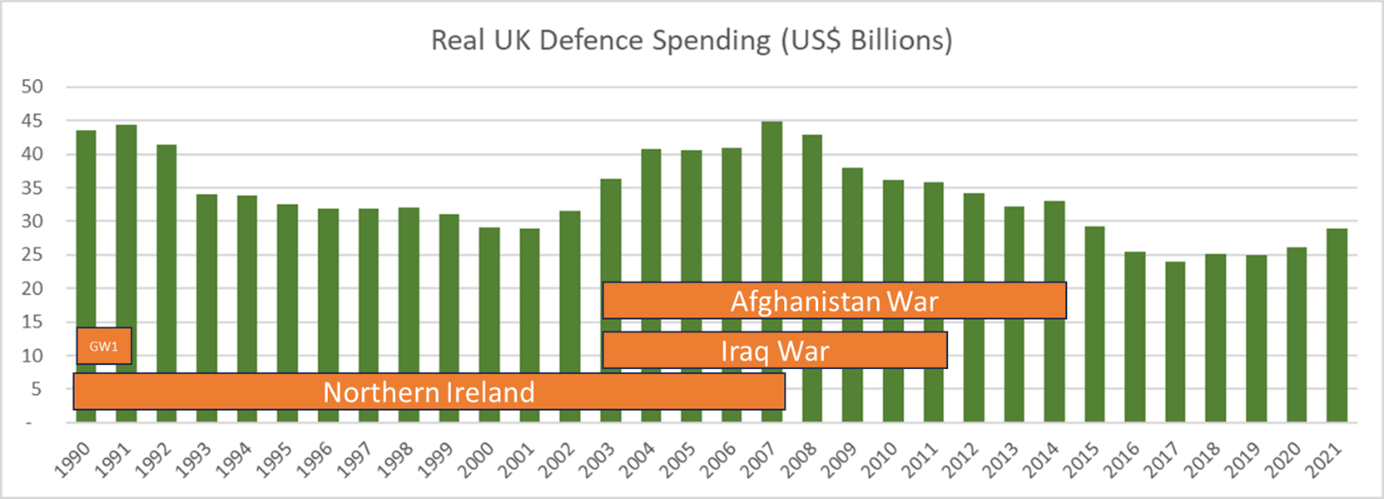

Only someone of Grant Shapps’ calibre would think that our Armed Forces are capable. Only a fool would make a virtue of spending “more cash than ever” – which of course ignores the impact of inflation. Across the economy £1 in 1990 is worth £2.85 today. The char below shows inflation adjusted UK defence spending; military capability has been bleeding away since the end of the Cold War (data from Macrotrends).

This is the best case as defence inflation is notoriously higher than the rest of the economy – not least to a lack of competition, ill informed customers (that is, the military who have made buying the wrong kit at the wrong price an art form) and political interference.

The graph shows the one thing that Shapps’ predecessor achieved; the first real increase in the defence budget in 15 years. Unfortunately the MOD is more than capable of producing black holes to consume it.

(Some of) The Threats

Russia

It is no secret that President Putin wishes to restore Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia to the Russian Federation. While Ukraine is a work in progress the Baltic states are more complicated for him to snatch overtly due to their membership of NATO and the crucial effect of Article 5 (which deems that an attack on one state is an attack on all).

No doubt Mr Putin’s ambitions are constrained by a desire to avoid nuclear Armageddon, a wish he shares with the rest of the planet, including the UK’s Prime Minister (who has sole authority to launch Trident), the President of France and the President of the US. Do either of those three regard the sovereignty of the Baltics worth a nuclear exchange? Or risking a nuclear exchange? Or spilling blood for?

To demonstrate their preparedness to fight for the Baltics the UK and other NATO members have created “Enhanced Forward Presence”. It comprises” just 4 multi-national battle groups , one each lead by the UK, The US, Canada and Germany based in Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Another four such battlegroups are being established in Hungary, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Romania lest Ukraine falls. (NATO has also forward deployed some air assets and it’s ships are often in the Baltic and Black Sea, but war is ultimately about the occupation of land and it’s the land forces that count).

These battlegroups theoretically augment the indigenous forces, which vary in capability. In the north, considered the most vulnerable due to the Suwalki Gap, that is a terrain corridor between Kaliningrad (the isolated part of Russia on the Baltic) and Belarus, a Russian Ally. The formidable Polish Army comprises 4 proper divisions totalling some 40 combat battlegroups, plus a full suite of supporting arms. The Baltic ones less so, totalling perhaps 14 regular battle groups plus about the same in reserves.

By comparison, Russia invaded Ukraine with 100 battle groups. For sure the Russian Army is somewhat depleted, but don’t forget it’s still winning – in as much as Russia occupies about 20% of Ukraine. The tanks Putin parked on the Ukrainian lawn are still there. Worse for the Ukrainians, Russia’s military production is geared up and western sanctions have not crippled the Russian economy.

Here’s the real challenge though – what would the West to if the Russian army simply avoided contact with the NATO units as it drove to the Baltic. That would leave one or more NATO battlegroups surrounded and logistically isolated. Whether they could fight out of such a position is questionable. It’s also not certain that the Russians would use that corridor, in which case much NATO thought is misplaced.

Ukraine

Mr Putin has already learned to mistrust generals who tell him that they can invade a country in three days. Mr Shapps should heed that, although I doubt British senior officers need to avoid fifth floor windows.

For all the western talk of super precision weaponry, high quality training and tanks and the efficacy of drones and cyber war Russia is winning the war. As western stockpiles of sophisticated weaponry dwindle (and those in Ukraine diminish further) Russia’s crude mass remains undiminished. Unless there is a dramatic change in Western policy it is probably the Ukraine will run out of soldiers and ammunition before Russia does, in which case it’s game over.

The one possible change would be if Ukraine received sufficient F16s (and supporting logistics and weapons) to arrange protracted air superiority over selected parts of the battlefield. Quite when the F16s will arrive and how many there will be remains shrouded in mystery. The consensus seems to be that they’ll get around 60 in total, with 18 arriving this spring. Whether this will turn the Russian tide or prolong Ukraine’s agony is anyone’s guess.

While western artillery production is scaling up, production lines for more sophisticated weaponry are more complex. The production lines must fill three voids – four if you count the Israelis.. Firstly the Ukrainians will use whatever they are give – they’re at war and if Russia is out next enemy killing Russians now in Ukraine could reduce and delay problems on the NATO borders. Secondly they need to replenish western stockpiles – the war stocks that were depleted to arm Ukraine. Finally, and worse, the West needs to look at the size of its stockpiles and consider whether they’re adequate. They probably are not, so the factories need to get busy and armies need to invest in ammunition storage.

(The Israelis, close allies of the US, are also at war. However the IDF has stockpiles and Israel has an effective arms industry. Moreover the IDF has probably passed peak consumption in Gaza).

The lesson is simple. As Voltaire said in the 18th Century, “God is on the side of the big battalions”. He modified it to “..big battalions who can shoot straight.” Modern industrial war also requires that battalions have adequate ammunition stockpiles. It’s hardly new – warfare is always as much about logistics as it is tactics.

If you run out of ammunition in a firefight you’ve become the fool who took a knife (or bayonet) to a gun fight. That’s the path to a body bag. Unfortunately this is just the course that Boris Johnson set us on.

The Red Sea

Last week Shapps went on to enthuse about the recent RAF air strikes in Yemen, seemingly unaware that both the aircraft carriers built to protect the freedom of the seas from Houthis and their ilk are tied up in Portsmouth Harbour due to a lack of crews. Does he not realise that until the RAF gets some airborne early warning of its own it is fit only for air

-shows, unless we’re working with an AWACS equipped ally?

Dropping bombs on people is always a favourite political response. Provided they have limited air defence it’s pretty safe (politicians hate body bags), pretty quick to arrange and makes the political look dynamic. While the incoming bombs will usually destroy what their aimed at and kill anyone close by, they can’t kill what they don’t see. Bombing campaigns seldom achieve conclusive results b themselves, as Western Air Forces have demonstrated repeatedly in the past 30 years. President Biden has already acknowledged that the Red Sea bombing will not stop the Houthi missiles despite the US Navy launching four more raids – without, it seems, a contribution from the RAF.

Operations in the Red Sea perfectly illustrate the Royal Navy’s main problems; it does not have enough ships and it can’t crew those that it has. HMS Diamond (an anti-aircraft Type 45 destroyer) has been busy shooting down drones threatening merchant ships. It is now to be supported by two other British warships, HMS Richmond and HMS Lancaster. Unfortunately both ships are Type 23 Frigates, optimised for anti-submarine warfare. As yet the Houthis don’t have submarines. Their air defence capability is designed for self-protection rather than area dominance; they can only protect merchant ships close to them.

How long these ships can stay there until relieved is a question best answered by looking at the Royal Navy in more detail.

The Fleet

The Navy has six Type 45s, none of which is “immediately available” to replace or augment HMS Diamond. Two (HMS Dragon and HMS Defender) are in refit. One is in the Caribbean, one in the med and one in home waters. Meanwhile it’s having to decommission two of its Type 23 Frigates due to personnel shortages, leaving a total of just nine. Aside from the destroyers and frigates the RN’s ocean-going surface fleet has two carriers, two commando assault ships (which are virtually unarmed and need escorts), eight offshore patrol boats and seven mine countermeasures vessels (of which one is broken in Bahrein).

It also has four nuclear missile submarines carrying the nuclear deterrent and six nuclear powered attack submarines, although it seems short of an admiral to command them.

The good news is that the Navy is getting new frigates, the Type 26 and the Type 31 – but they will be useless without crews. Even if all the ships were crewed the force is rather out of balance, being desperately short of anti-air vessels (necessary to protect the carriers and landing ships) and frigates. Having splashed its budget on carriers, deleting a requirement for six Type 45 destroyers to pay for them, it’s now utterly dependent on the RAF to make them credible.

The Air Force

Unfortunately things aren’t great for the RAF either. It’s new F35s won’t reach full operating capability until 2025 – meaning that much of the hangar space on the aircraft carriers can only be occupied by US Marine Corps F35Bs (the US Navy operated the F35C which can’t land on a British Carrier)[1].

The RAF’s aging Typhoons have serviceability issues and a quarter of them are being retried early rather than upgraded, a controversial decision. Disastrously the RAF also lacks AWACS, the system used to find enemies and control the battle. It scrapped the ubiquitous E3 Sentry in 2021. It intends to replace the seven E3s with just three E8 Wedgetails (which is not enough to provide continuous cover). Sue in 2023, none has yet been delivered.

That’s all pretty grim. On the up side, at least the Navy and RAF have a reasonably clear purpose, even if they lack the kit, training time and personnel.

The Army

The Army doesn’t seem to know what it’s for. While it was busy losing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan while finally forcing the IRA to a ceasefire, it persuaded itself that armoured warfare was a thing of the past. It tried to build a concept called “Strike”, but that was floored by the problems with the Ajax vehicle and delays in purchasing Boxer. The strike idea gently vanished in another cut. “Cyber” and “network centric warfare” became buzzwords and the drone fanatics had their day.

Then Putin’s tanks rolled into Ukraine, capturing 20% of it in a matter of days. Eventually in 2022 the head of the Army had to state the obvious, that one can’t cyber one’s way across a river. Armoured warfare is back, although most of the British Army seems unable to grasp that. Which is odd, as Joe Taxpayer has been paying for an armoured division since the end of the cold war. In 2023 Parliaments Select Committee on Defence Army finally admitted in passing that the UK has not been able to field an armoured division since 1991 . A combination of rundown, defence cuts and general idiocy converted military capability into a Potemkin village.

OF course, the lack of the capability didn’t prevent us paying to have an armoured division[2] headquarters all the while. In fact the Army has three divisional headquarters, which report to HQ Filed Army who in turn reports to Army Headquarters. Top heavy is an understatement.

Excluding the special forces bits, the Army’s combat power now comes in the form of Brigade Combat Teams. It has one deep strike brigade combat team, two armoured ones, one light mechanised one and light one and an air assault one, a total of just six. The can’t all be deployed simultaneously and they can’t be deployed for protracted periods without having to rotate back for rest.[3]

The deep strike brigade is waiting for the disastrous Ajax reconnaissance vehicle and has no deep strike other than possible attack helicopters, which haven’t thrived in Ukraine. The armoured ones are waiting for the Challenger 2 to be upgraded and for their Warrior infantry fighting vehicles to be replaced by Boxer, which is either revolutionary or brilliant.

Most of the army’s fighting strength (in terms of headcount) lies in the infantry. Of the 33 regular infantry battalions just five are armoured. Two more are wheeled and the rest fight on foot, just like their forebears on the Somme, albeit some arrive by parachute.

Four battalions of Rangers perform quasi special operations and another four Security Force Assistance battalion exist to train and support the less capable armies of friendly powers – for example deploying to Nigeria to fight against Boko Harem.

In value for money terms this doesn’t compare well with the 55,000 strong Cold War Army in Germany, which deployed 12 combat brigades in four divisions, plus an artillery division, a corps headquarters and the base of an army group headquarters[4]. It was more or less up to strength, well equipped and at high readiness (it could go to war at six hours’ notice).

Strangely, or perhaps inevitable, the ability to deploy perhaps two brigades requires two full Generals, ten Lieutenant Generals, 52 Major Generals and a staggering 151 Brigadiers. Whatever else Tommy Atkins lacks it’s not someone to tell him what to do.

(To be fair, it’s not just the Army that has this astonishing number of senior officers. The Navy’s 60 ships and crew are supervised by 3 Admirals, nine Vice-Admirals, 30 Rear Admirals and 75 Commodores. The RAF has two Air Chief Marshals, Seven Air Marshalls, 31 Air Vice Marshalls and 84 Air Commodores - almost one per working jet).

It’s hard not to conclude that the armed Forces are almost beyond recovery, just as the Army was after the Crimean War and(again) after the Boer War. It recovered after those debacles at the behest of two able Secretaries of State, Cardwell and Haldane respectively. Neither Wallace nor Shapps are anything like their calibre.

Solutions

It’s depressingly easy to criticise the armed forces in their current state. The question is what to do about it and how to fund it. Herewith some suggestions. They’re necessarily brief and will upset lots of people.

Recruitment and Retention

Good leaders don’t outsource problems, yet the Armed forces rely on Capita. Rather than blame their hapless supplier (who is far from blameless) the services need to take direct and personal responsibility for recruitment and retention. It should become a command responsibility, as it once was for much of the Army. The unit you command has low recruiting / high wastage? You had better fix it. That means getting in touch with your recruiting areas and staying in their minds. For sure schools should be required to allow armed forces recruiting teams to visit. Introduce a GI bill – you serve five years (or so) and we’ll pay for/pay off your university bill.

Recruiting Gen Z and millennials seems harder. Whether it arises from lockdown, wokeness or generational change whereas my generations soldiers joined the Army to see the world it now seems that soldiers want to join but stay close to home. Lowering entry standards – as has been mooted - might be sensible, but the challenge is delivering trained service personnel to the forces, not filling recruit intakes to capacity with a higher proportion of those who are likely to fail.

Lowering the standards for officers, as has already happened, is a path to disaster. It’s very hard for to simultaneously train and test anyone – when they stuff up, as officer cadets are wont to do, do you invest further in remedial training or bin them due to lack of ability? Certainly the last thing an army that is haemorrhaging manpower needs is weaker junior leadership. The Army Officer Selection Board is one of the few bits of the entire military that works well; if they say fail they mean it.

Finally I would look at pay and conditions. That may well increase spending – pay is about 25% of the defence budget – but the armed forces are in a competitive market. (That’s off, usually economic depressions benefit armed forces recruitment).

All of that will take time and none of it will solve the Navy’s problems, which are close to a national emergency if you believe in freedom of the seas. My temporary answer that to rebadge some of the light role infantry as sailors. As well as affording the taxpayer some value from their salary there is a precedent, sort of. In 1740 during the War of Jenkins’ Ear 500 Chelsea Pensioners were pressed into service aboard Lord Anson’s ships.

Structures

The armed forces are of necessity hierarchical and very aware of ranks and who is in charge. However there is always a tendency to have too many headquarters.

I’ve cited the Army’s maintenance of multiple divisional headquarters tor 30 years despite not having a deployable division. I would be astonished it such top heaviness were not prevalent in the other services. The layers of management that lie above combat command tend to generate, just as all bureaucracy does. This is not just a problem in the MOD – it runs across government. That’s not an excuse. In comparison Amazon, the world’s most valuable companies with global operations and around 1.6 million employees gets by with just 12 executive officers.

It's quite possible that the best talent the Armed Forces is leaving before it reaches the top. (That at least would explain the Navy’s submariner admiral problem). Clearing out the placeholders and deadwood from the top would give them a cause to stay. Changing the posting cycle, where senior officers change job every two to three years is inefficient, why not keep them in post? Similarly there are a plethora of headquarters that are, at best, replicating the efforts of other ones or simply filling in gaps so that brigadiers report to major generals who report to lieutenant generals who report to generals. None of the sixty four generals command combat formations (although two pretend that they do) so there is no military reason not to radically flatten the structure.

There needs to be more clarity on what the reserves are for and how many we need. Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq were largely only possible due to the availability of trained reservists to fill in manpower gaps. That became increasingly expensive for the army and the economy; it is the nature of a reservist that they hold down a demanding job – replacing them in that job while they’re on operations is a cost and likely a drop in productivity. There is some evidence that after operations reservists find it harder to readjust than their regular comrades. (Unsurprising really, the regulars remain close to those with shared experience. The reservists are tossed back into the uncomprehending civilian world). The armed forces would be better serviced by full recruitment.

Equipment

The Navy needs more frigates and destroyers almost as much as it needs more sailors. Order them and keep the production lines open. (Warships are actually one of the few things that British heavy industry does well). Whether two carriers and two assault ships is a sensible use of scant funds needs sceptical external analysis.

The RAF needs more Wedgetails. Whether it needs more F35s, whether they need to land on aircraft carriers and whether they need to do that vertically is an open question.

The army probably needs more tanks that the 147 Challenger 3 (enough for one armoured brigade – NOT a division - and some training) that it’s budgeted for, as well as more Boxers than its ordered and more artillery. It needs to learn to buy off the shelf efficiently and it needs to rebuild and expand its ammunition stockpiles.

Costs

I doubt much can be achieved within the existing budget and there is far more spending required than this short post has space for. However, like policing and law making, defence is one of the few areas of government that only the government can do. It’s a disgrace that it simply hasn’t been doing it.

Whether the Russian (and other) threats are nascent or imminent, it’s time for the armed forces to get real and get training. Given the likely impact on taxation and the looming election a wise government (ha!) would secure public support.

Parting Thoughts

The belief that the end of the Cold War meant an outbreak of peace and reduced spending was a delusion. Frittering away the “peace dividend” on the twin black holes of the NHS and the welfare system was reckless. Given that they are also broken that spending was pointless too.

In some ways sorting out the MOD is easier than most other ministries as its activities do not impact on most people most of the time. The problems are not just funding and it’s never a good idea to throw failing organisations good money after bad.

It can be done if there is a will, more money (in real terms) and a Secretary of State of sufficient calibre. None of the current inhabitants of Westminster spring to mind.

[1] the US Navy opted for the F35C which requires the steam catapult arrestor wires of conventional carriers. It’s possibly another area of British exceptionalism – c.f. the NHS – and it may be that “cat and trap” will be retrofitted,

[2] A division used to be the standard unit of military power. It comprises tanks, artillery and all other unit types. IT typically comprises a headquarters and three or more brigades. A brigade comprises a headquarters and three of four battle groups, each of which is based on a battalion. Rough strengths are 15-20,000 in a division, about 5,000 in a brigade and about 1,000 in a battalion.

[3] Rotating for rest is sound policy. It’s notable that the British Army tours are about 6 months, the US Armed forces for about a year.

[4] In this context a corps is two to five divisions. An Army Group is two to five corps.

Well, that was a brilliant in-depth article, to the very high standard of Patrick Benham-Crosswell.

One point.

Whilst Port Talbot did not serve the core strategic needs of steel production, surely the 8 year wait for glorified electric arc scrap melters to replace the current blast furnaces put us at risk. So, if we do get into difficulty, should we ask China for steel?

How about Russia?

France?

Eire?

Don't ask the politicians..... or the Civil Service......